Key points:

- Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), growth stocks have outperformed value stocks significantly. This follows a long period of outperformance for value.

- Whilst the “tech bubble” made some investors weary of technology and growth companies, valuation levels for tech companies today are significantly lower than 20 years ago. Further, investors should look at the earnings certainty of industry incumbents through that same critical lens.

- We believe there is a strong argument that the structural tailwinds which have assisted growth stock investing will continue.

Proponents of global value investing have endured a torrid time following the GFC with value underperforming growth eight out of the past ten calendar years. At the time of writing, value had underperformed growth by over 87% since relative outperformance peaked in 2007. Underperformance of this magnitude is uncommon, but not unprecedented, with the decade prior to the technology bubble being a golden period for growth investing, only to reverse sharply in the years that followed.

This leaves us at an interesting juncture. Does growth investing continue its outperformance? Or does the value premium return to reign again?

Value investing and the value premium

The roots of value investing as we know it today can be traced back to Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor [1]. This book has been essential reading for investing enthusiasts for decades, with Graham’s theories centred around the intrinsic value of a company being heavily linked to its book value.

The term “value premium” gained further attention in 1992 following a study from Fama and French [2] which showed stocks with a low price to book value outperformed stocks with a high price to book value. For many years, the MSCI World Growth and Value indices, which have data going back to 1975, seemed to corroborate Fama and French’s thesis. At its relative peak the value index level was 80% higher than the growth index though recently the cumulative growth and value indices have converged. In other words, growth and value stocks have delivered near identical aggregate performance since 1975.

Source: MSCI, Bloomberg

Growth investing is based on finding stocks where growth is under appreciated. Investors particularly underestimate the value of compounding earnings growth over time. Many investors are attracted to near term trends, to yield, and to value.

A changing world hasn’t helped value stocks

There is little doubt that the adaptation of technology is happening more quickly, and technology is transforming sectors across the board. This is increasingly a zero-sum game. For every success that technology is enabling, there is a company on the other side being disrupted. Be it Blockbuster making way for Netflix, Borders making way for Amazon, traditional media and advertising making way for Facebook and Google, Nokia making way for Apple, or bricks and mortar stores losing ground to online shopping. This is one of the key issues for value stocks, they are being disrupted by growth companies.

One must question what traditional value investors like Benjamin Graham would make of the world in 2019. What would he make of the world’s largest retailer owning no inventory, the world’s largest taxi company not owning any cars and the world’s largest accommodation provider owning no hotels? While we will never know the answer, we can get some guidance from Graham’s most loyal disciple, Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway recently acquired $900m worth of Amazon stock, a stock that trades at around twenty times its book value, thus unlikely to meet Graham’s definition of value. Charlie Munger, Warren Buffet’s right-hand man, goes a few steps further and describes Benjamin Graham disciples as being:

“…like a bunch of cod fishermen after all the cod’s been overfished. They don’t catch a lot of cod, but they keep on fishing in the same waters. That’s what happened to all these value investors. Maybe they should move to where the fish are…”

Tackling this changing world….and finding the cod

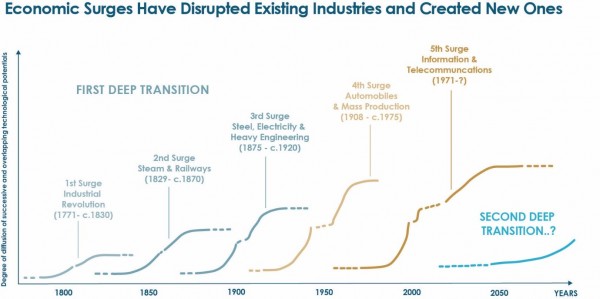

While terms such as “technological disruption” are relatively new to the investment vocabulary, economic surges which challenge existing business models are not (see Figure 2). Throughout time we’ve had surges of development which have lasted decades.

Figure 2: Deep economic surges

Source: Deep transitions: Emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Scott and Kanger, 2018.

Instead of viewing technology as a sector within the equity market, we need to view its impact in a much broader sense, as technology is impacting business models across every sector within the global market.

Even though we are almost five decades into the age of information technology and telecommunications, the rate of change and innovation is faster than the most creative among us could have even imagined a decade ago. Netflix’s latest movie release, Murder Mystery, was watched by over 30 million households in its first three days. By comparison, 24 million movie tickets get sold in North America per week. Tesla just announced they delivered 95,200 cars in Q1, almost 15 times more than they did the same quarter five years ago. Today Amazon and Alibaba have stores which have neither check outs nor cash payments; customers simply scan their phone on entry, select what they want, and their credit card is charged automatically.

This change is hard to anticipate. Our global equity partner, T. Rowe Price, first bought Amazon at US$59.50 a little over a decade ago. Amazon’s valuation a decade ago was “expensive” on traditional measures, especially compared to existing retailers such as Barnes and Noble. Ten years later, Amazon’s share price is about 33 times higher while Barnes and Noble is worth about a third of it was. Today, similar comparisons are drawn between Tesla and existing car companies which specialise in internal combustion engine vehicles.

The last time growth performed this strongly it didn’t end so well.

It would be remiss to talk about growth investing without talking about the tech bubble that burst in the early 2000’s following a period of outperformance for so-called “growth” stocks. When one looks at the price to earnings ratio during the early 2000’s (Figure 3), we can see the level of optimism that was priced into those stocks. Looking at this today, along with a wide range of valuation metrics, we see little commonality between then and now, especially considering where interest rates are.

Figure 3: P/E Ratio of global growth stocks.

Source: MSCI, Bloomberg.

Navigating markets from here

“The secular forces powering the technology sector are robust and here to stay. The pace of innovation remains breathless”

Scott Berg, Portfolio Manager, T. Rowe Price

There is little evidence that the secular changes which have benefited growth stocks are abating. However, that doesn’t mean that growth companies are immune to change, nor that we should ignore all tenants of value investing. It also doesn’t mean that investing in a “Nifty Fifty”-like mix of technology companies is the answer to navigating the years ahead. What it does mean is that, in a period where, on average, we are paying 16 times the next twelve months’ earnings for a global listed company, we must view the earnings of those companies through a critical lens taking into account the speed of change that comes with deep economic transitions.

[1] First published in 1949 by Harper & Row Publishers, New York

[2] Published in the June 1992 edition of The Journal of Finance entitled The Cross‐Section of Expected Stock Returns

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

Harbour Asset Management Limited is the issuer and manager of the Harbour Investment Funds. Investors must receive and should read carefully the Product Disclosure Statement, available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. We are required to publish quarterly Fund updates showing returns and total fees during the previous year, also available at www.harbourasset.co.nz. Harbour Asset Management Limited also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a Wholesale Investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013. This publication is provided in good faith for general information purposes only. Information has been prepared from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication, but this is not guaranteed. Information, analysis or views contained herein reflect a judgement at the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. This is not intended to constitute advice to any person. To the extent that any such information, analysis, opinions or views constitutes advice, it does not consider any person’s particular financial situation or goals and, accordingly, does not constitute personalised advice under the Financial Advisers Act 2008. This does not constitute advice of a legal, accounting, tax or other nature to any persons. You should consult your tax adviser in order to understand the impact of investment decisions on your tax position. The price, value and income derived from investments may fluctuate and investors may get back less than originally invested. Where an investment is denominated in a foreign currency, changes in rates of exchange may have an adverse effect on the value, price or income of the investment. Actual performance will be affected by fund charges as well as the timing of an investor’s cash flows into or out of the Fund. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. Neither Harbour Asset Management Limited nor any other person guarantees repayment of any capital or any returns on capital invested in the investments. To the maximum extent permitted by law, no liability or responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage, direct or consequential, arising from or in connection with this or its contents.