- The US has announced a more aggressive than expected increase in import tariffs, which incorporates a reciprocal tariff programme with a minimum 10% on all countries, including Australia and New Zealand.

- If tariffs are maintained at these newly announced levels, we expect them to lower already-decelerating US GDP growth and increase inflation pressures. Global growth is likely to fall as a result of this US weakness and as economies elsewhere experience reduced US demand for their exports to varying degrees.

- While these tariffs will be implemented in the next week, comments from US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent left the door for lowering tariffs slightly ajar, in stating "As long as you don't retaliate this is the high end of the number".

- Despite our tariff rate being at the lower end on a global scale, this is still not great news for NZ export demand. The US is our second largest trading partner, and we have a heavy reliance on the countries that are involved in this trade war.

US President Trump’s “Liberation Day” has seen the US announce more aggressive than expected increases in import tariffs, which incorporate both reciprocal and minimum 10% tariffs on all countries, including Australia and NZ. These will be implemented over the next week though comments from US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent left the door for lowering tariffs slightly ajar, in stating "As long as you don't retaliate this is the high end of the number". Imports of Australian beef have also been banned. Among the big economies, China was hit hardest with an additional 34% tariff announced to go on top of the 20% already delivered by the Trump 2.0 administration. There is uncertainty about whether the Trump 1.0 tariffs on China are captured in these numbers. If they are not and you add the 14.5% effective tariff from Trump 1.0, the total effective tariff on China becomes 68.5%. Europe was also punished with an additional 20% tariff. For China, the high tariffs imposed on Southeast Asian countries also reduces the prospect of redirecting exports to the US via these markets (as has been the case since Trump 1.0). Interestingly, Canada and Mexico have been exempted from additional tariffs, for now, except for those already in place.

If tariffs are maintained at these newly announced levels, we expect them to lower US GDP growth and increase inflation pressure, it’s just a question of quantum. The US economy has already been slowing and most now see a US recession as a real risk. The wrinkle for the Federal Reserve, however, is that the tariffs are likely to lift inflation. Citibank, for example, expect the tariffs to add one percentage point to core inflation, taking it to 4% this year. The market expects lower growth to dominate the Fed’s thinking and implies more than 100bp of rate cuts over the next year.

We expect global growth to fall as US households and businesses respond to higher prices, while economies elsewhere experience lower US demand for their exports to varying degrees. Asia, for example, appears to have had the largest imposition of an increase in tariffs. Inflation rates outside of the US may fall as global demand moderates and goods destined for the US are redirected to other markets, placing downward pressure on prices for goods. Imported goods from the US, however, may increase in price due to input price inflation caused by the tariffs. This leaves aside both the impact of any retaliatory tariffs and the potential deflationary impact of lower global growth.

Financial markets are taking the news badly. The US effective tariff rate will now rise to around 25%, much higher than the c.10% expected by markets. While it’s not clear that Trump has an ultimate plan, he clearly believes that the US is being taken advantage of by its trading partners who run trade surpluses, aided by large tariffs on US goods and undervalued exchange rates. At the time of writing, US equity futures have dropped 3% from Wednesday’s close and US yields are 10bp lower, likely conflicted by the negative growth implication but upside inflation risk. The US dollar is currently broadly unchanged with safe-haven support offset by lower US growth expectations vs. the rest of the world. The NZ equity market has been remarkably resilient down less than 0.5% and NZ bond yields are down around 10bp, with the market now pricing the OCR to be below 3% in November this year. This seems appropriate to us given our view was already that the NZ economy may need more help than interest rate markets were implying (for further discussion, see Harbour Navigator: NZ out of recession but risks remain skewed to lower rates, 24 March 2025). In respect of one of the larger companies in the New Zealand market, with a high amount of US sales, it looks like Fisher and Paykel Healthcare may be exempt from any new tariffs on Mexico via the trade agreement between the US, Mexico and Canada. United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) compliant goods face 0% tariffs and we understand most of its production is USMCA compliant.

Our broad asset allocation remains underweight growth assets, with a strong bias to underweight global equities. We see no reason yet to change that stance.

What does it mean for NZ?

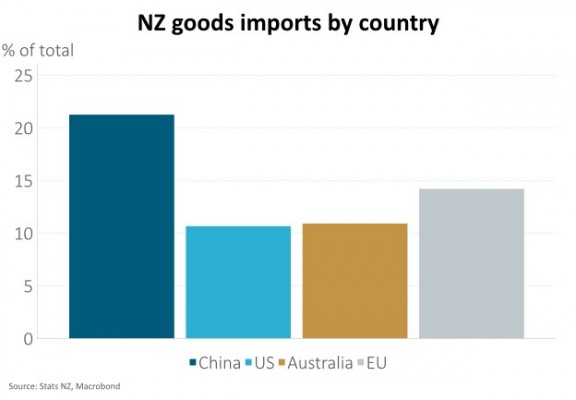

How does New Zealand come away after Liberation Day? The short answer is that despite our tariff rate being at the lower end on a global scale, it’s still not good news, we are a small open economy with a heavy reliance on the countries that are involved in this trade war. The US is our second largest goods export destination (see chart above) with the composition heavily skewed towards primary goods (see chart below). NZ exports $9bn of goods to the US each year, around 2.2% of our GDP. NZ will now have a 10% tariff applied to these goods likely reducing US demand for some of these products where close locally made substitutes are available. If the tariffs are passed on to US consumers and they reduce demand by 10% to offset the price increase, it represents a 20bp hit to GDP, all else equal. For beef, however, we may benefit from the ban on Australian beef as the US looks to find alternative sources.

The indirect channel may well matter more for NZ economic growth as higher global trade tariffs may reduce global growth and demand for our exports. Tariffs act like a tax, lowering overall economic prosperity. If importers choose to absorb the higher costs, their profitability suffers. If the tariffs are passed on, households and businesses will reduce their demand for the affected goods and services. Central banks may be able to help via lower interest rates but for the US, the associated inflation pressure of tariffs may limit the US Federal Reserve’s capacity to help.

There is also a confidence channel to consider that likely impacts all countries, including NZ. If households and businesses remain unsure about the future direction of global trade policy they may choose to delay spending, as we have observed in recent months. This channel only strengthens in the case where global asset prices remain under downward pressure.

Our exporters may also be hurt by reduced competitiveness if we see NZDUSD appreciation, driven by broad-based USD weakness as US exceptionalism withers and its economic prospects converge with the rest of the world. We think there is plenty of room for appreciation given NZDUSD currently sits around 15% below our long-term fair value estimate, based on purchasing power party. If risk sentiment deteriorates sufficiently, however, safe-haven demand for the USD may provide an offset.

From an import point of view, NZ may benefit as goods are re-directed to countries that are not imposing tariffs. For example, Chinese-made electric vehicles that were destined for the US may find their way to these countries at discounted prices. Imports from those countries imposing tariffs may become more expensive, however, as firms look to pass on higher input costs.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

This publication is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided is not intended to be financial advice. The information provided is given in good faith and has been prepared from sources believed to be accurate and complete as at the date of issue, but such information may be subject to change. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made regarding future performance of the Funds. No person guarantees the performance of any funds managed by Harbour Asset Management Limited.

Harbour Asset Management Limited (Harbour) is the issuer of the Harbour Investment Funds. A copy of the Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://www.harbourasset.co.nz/our-funds/investor-documents/. Harbour is also the issuer of Hunter Investment Funds (Hunter). A copy of the relevant Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://hunterinvestments.co.nz/resources/. Please find our quarterly Fund updates, which contain returns and total fees during the previous year on those Harbour and Hunter websites. Harbour also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a wholesale investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.