You might think that our title is provocative, and a fringe view. But this was a consensus question from investors and analysts after our research visit to Australia in the week before Easter.

-

Regulation has encouraged bank lending to become more conservative, more housing focused and increasingly outsourced through broker channels.

-

Regulators seem to want even less bank risk and more financial stress tests.

-

As a result, bank credit quality remains very strong despite obvious stress emerging among many households.

We travelled to Sydney in the week before Easter[1] to explore these fundamental questions:

-

Has regulation squashed the loan impairment cycle? Are bank loan impairment provisions too generous in the context of ongoing low unemployment and a strong housing market?

-

What is the competition environment like in Australia given the background of the NZ Commerce Commission report on bank competition in retail banking? Where is the innovation? How are the banks and regulators facing into the current market?

-

What has been driving the recent surge in Australian listed bank share prices? What are we missing?

In this article we explore the first of these questions. Are banks over-indexing to safety?

If one quote captured the essence of our research trip, it was Ross McEwan’s (outgoing NAB CEO) comment,

“I think we are in for another round of unintentionally making it more and more difficult and more expensive for banks to deal with customers who need us”.

Following the GFC (global financial crisis), the banks have been swamped by regulatory inquiries in Australia into a vast array of business practices. In the last dozen years, the bank sector has traversed the risk-taking squabble outlined in the Murray Report on improving Australia’s financial system which recommended the establishment of a path to ‘unquestionably strong’ capital as banks exited the GFC.

The Hayne Commission then took no prisoners in the public flogging of misconduct failures which resulted in the switch out of many bank Chairs and CEOs, together with their senior management teams. The strategic direction was largely reset by these incomers with key words and phrases like “simplification” and “back to core banking”.

Under heavy regulation some banks shrunk their business lending focus as new capital adequacy risk-weights encouraged lending to housing and especially low LVR and owner-occupied housing[2].

In the last six months investors in the Australian banks have been rewarded with relatively high total shareholder returns. The controversies in the bank sector between regulators, CEOs and investors remain in the headlines across the media with the recent addition of the Shadow Treasurer, the Hon. Angus Taylor adding his voice to the problem of the over-reach of banking regulators in stymieing innovation and lending. In his address to the AFR Banking Summit, Taylor said that the banking “regulatory grid had gone too far”. Taylor’s argument is that a very well capitalised banking sector should not be hobbled by a risk-averse regulatory structure which stops in its tracks the idea that banks should take risk and be a key allocator of scarce capital.

Over regulation is making it difficult for many borrowers.

-

Australia is objectively one of the hardest markets in the world to take out a credit card – Matt Comyn

-

My fear as I look back: we are pushing too many people outside banking – Ross McEwan

-

Credit quality has not reacted to higher interest rates – Peter King

-

Lending is becoming the domain of affluent people – Antonia Watson

And with the background of only sub-5% Australian bank credit growth, and a concentration in secured lending, questions of the right type of competition and regulation of the banking system seem to be swinging the pendulum back to considering policy settings.

As the head of the Australian Banking Association, Anna Bligh noted, if the bank doesn’t take that risk, what happens to the borrower? They go to the “less regulated non-bank system, paying higher interest rates with less support and protection through regulated hardship programs”.

Banks are likely over provisioned into a soft landing

In 2023, the battle with inflation and the brief appearance of cracks in the global system probably ought to have been the key factors influencing banking sector narratives in Australia, but in fact angst over Australian mortgage price wars dominated headlines (with extra-ordinary discounting and even cash-backs for switching).

Some banks have continued to beat the drums about a potential loan impairment cycle. In their latest earnings reports or Pillar 3 capital updates, banks retained their forward-looking projections of potentially higher unemployment, and therefore maintained high loan provision overlays despite no tangible evidence of higher bad or doubtful debts.

New responsible lending standards have provided another layer of bank regulation which seems to have lessened the evidence of risk in bank balance sheets. Banks developed large provisioning buffers (some would say excessive) against potential non-performing loans through the Covid period. They have been reluctant to alter that provisioning position as economists have warned about the interest rate cliff facing borrowers moving from very low fixed rate mortgages to much higher floating and reset fixed rate interest rates.

While monetary policy acts with a lag, borrower stress has been very benign, especially in Australia. Many households have large savings buffers; deposits at Australian banks are some $400bn higher than pre-Covid; now unemployment is sub-4% and house prices generally are higher.

Banks we spoke with directly, say most of the pain on mortgage rates resetting has happened with only a fraction yet to reset in the coming quarter. In Australia mortgage competition has also cut the effective rate rise faced by borrowers by about a further 50-60 basis points (0.5% to 0.6%), and many households (estimated at more than 60% of total lending) are still well ahead on their repayment schedules. The core unanswered question we sought views on was whether lending standards had fundamentally altered the bank sector’s risk profile. Responsible lending standards have been biting for about four years, combined with LVR restrictions, higher documentation on loans and more detailed requirements on lenders. The evidence so far is that bank loan quality remains high.

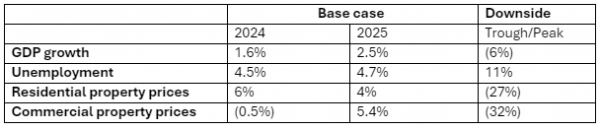

Last reported credit loss ratios are near cyclical lows ranging from 3bps to 12bps across the major banks. The last 20-year average has been 19bps to 29bps of annual credit loss. And additionally, in the development of collective provisioning banks appear to have an unusual bias to a large downside scenario. For instance (and not to call out just one bank) Westpac have attached a 45% probability to their downside risk profile which entails a 6% collapse in GDP and the unemployment rate hitting 11%. These forward-looking scenarios and the inclusion of a high stress economic scenario encourages banks to hold onto high provisioning, which to all intents is just a non-cash negative asset on their books which smooths earnings.

Forecasts used in Westpac’s most recent economic scenarios

Source: Westpac, February 2024

Against a risk weighted asset (lending) base the major banks hold between 1.35% and 1.65% in provisions against their loans.

UBS recently outlined the potential one-off impact on non-cash earnings from economic outcomes settling on only the base cases of the banks’ economic scenarios. They estimated the non-cash earnings could have one-off boosts of between 13.5% to 24.7% amounting to about 2-3 price earnings (PE) points.

We tested some of the banks on the practicalities of a write-back in provisions; and there seems to be a huge reluctance to significantly change provisions. In part, this reluctance to adopt a less conservative provisioning stance may also reflect the ongoing process of APRA (Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority) stress testing the banking system for a range of shocks where both existing provisions and capital buffers are challenged. There was some concern that the current rise in impairments in New Zealand could still portend a more difficult path for the Australian economy. To our thinking this seemed to be clutching at thin air given the marked differences in economic performance across the Tasman at present.

As part of our three-pronged analysis of contemporary banking sector issues, the questions we asked around the interaction of the very low bad debt and impairment cycle and the provisioning stance of the banks had the surprising industry response. Bad and doubtful debt is likely very low as a result of the risk averse nature of the banks. Any actual impairment cycle may be dampened significantly by the behavioural changes in lending, while at the same time banks have been encouraged to set aside very significant loan loss provisions against a future cycle that increasingly looks unlikely to eventuate.

The punchline in our conclusion suggests very little seems likely to change under the current stance of politicians and regulators, while we now also think that the market is well aware of the provisioning stance of the banks. This week, we asked banking analyst, Jon Mott of Barrenjoey whether a non-cash write back of provisions could be a catalyst for further bank share price appreciation. We follow that response and the perspectives of other analysts on a range of bank share price valuation influences in our final article in this series.

Meanwhile, we will shortly also publish our take on bank competition in the mortgage and deposit markets in Australia, and what that teaches us about the New Zealand Commerce Commission’s draft market study into personal banking services.

[1] Our research programme involved visits to meet executives at the large consumer lenders, Westpac and CBA, together with the challenger bank, Macquarie. We meet also with mortgage lenders and four industry analysts. This core programme was supported by our attendance at the tenth AFR Banking and Financial Summit, which brings together the bank CEOs with the full suite of regulators, and panel sessions on aspects of lending, the housing market, the non-bank sector, the payments system, and where AI might challenge business models.

[2] More recently, business lending has picked up, with banks utilising data and responding to a competitive thrust from some challenger brands.

IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DISCLAIMER

This publication is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided is not intended to be financial advice. The information provided is given in good faith and has been prepared from sources believed to be accurate and complete as at the date of issue, but such information may be subject to change. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made regarding future performance of the Funds. No person guarantees the performance of any funds managed by Harbour Asset Management Limited.

Harbour Asset Management Limited (Harbour) is the issuer of the Harbour Investment Funds. A copy of the Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://www.harbourasset.co.nz/our-funds/investor-documents/. Harbour is also the issuer of Hunter Investment Funds (Hunter). A copy of the relevant Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://hunterinvestments.co.nz/resources/. Please find our quarterly Fund updates, which contain returns and total fees during the previous year on those Harbour and Hunter websites. Harbour also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a wholesale investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.