- Consumer sentiment in China remains cautious post-pandemic, with spending reluctance despite crowds being back to normal.

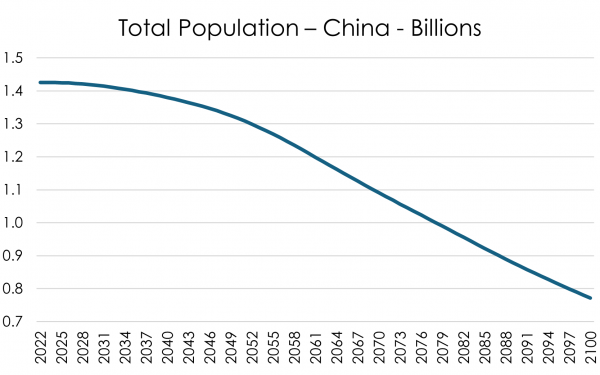

- Demographics are shaping long-term views of consumption and investing, with the UN’s central forecast projecting China’s population to halve over the next 75 years.

- Policy initiatives will be closely watched to see whether these can offset the structural changes occurring and, of course, a cyclical recovery might help too.

We were back on the ground in China in May, looking for signs that the weak consumer sentiment experienced last year would be on the improve. Meeting with many consumers, it is clear Mr and Mrs China are still being cautious about finances and their view on the economic outlook.

Whilst many things have normalised post-pandemic, most notably the crowds are back, the consumer is still very much reluctant to spend. Worried about income growth; employment; cost of child-care, education, aged-care, and healthcare; consumers are hesitant parting with hard-earned cash.

Many of these concerns could potentially be rectified through a cyclical recovery as China’s economy benefits from the resumption of global growth. Good policymaking could also help release significant excess savings held by Chinese households. However, concerns remain about structural changes to the economy, including demographic pressures and related property market weakness, which are driving sustained changes to consumer behaviour.

China’s population peaked recently and is now in decline. The United Nations’ central forecast is for China’s population to halve over the next 75 years. This is a confronting reality for both policymakers and Chinese consumers.

Source: United Nations Population Division

Commentators often draw parallels to China’s similarities (and differences) to that of Japan’s demographic profile, which saw deep structural problems manifest in the 1990s that have lingered ever since. We can see merits in both sides of the debate, although we have been surprised by the feedback from Chinese consumers on how demographics are shaping their long-term views of consumption and investing.

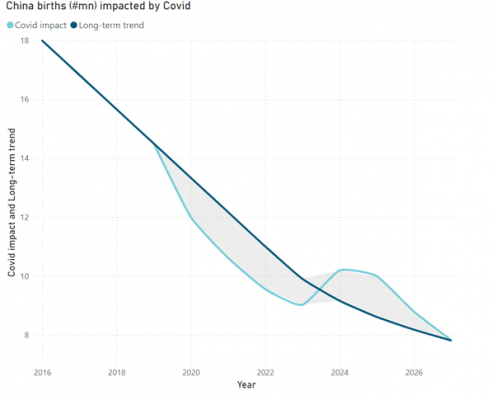

For almost four decades, the one-child policy reigned supreme in China. The impact of removing the policy in 2016 saw a short-lived blip in the birth rate before returning to its declining trend. Young Chinese tell us that having one child remains culturally embedded and increasingly young couples are choosing to not have children at all.

Today’s young Chinese have grown up with up to six adults supporting them with financial and care-taking responsibilities. Many of these children are now young adults, coming to terms with the familiar family unit being flipped to a scenario of they themselves potentially having to provide for multiple ageing family members in the years ahead. These prospects translate to more savings, less consumption and an increasing preference for not having children on their own.

Worried that healthcare and aged care is under-developed to care for the ageing population, self-insurance via excess savings is a systemic problem. Similarly, the urban residency system known as Hukou also means rural workers in the urban centres do not get access to social and health services. Policies to reform the Hukou system and aged-care services have the potential to release significant amounts of capital if households and rural workers can feel confident enough to not having to self-insure future welfare needs.

Companies like the a2 Milk Company, whose primary business is selling infant milk formula to Chinese families, are facing continued declines in the number of newborns. The number of women of child-bearing age is declining at a rate much faster than that of the overall population, which in the absence of significant policy changes and better economic outlook will translate to fewer births.

However, it is not just doom and gloom for a2 Milk as near-term expectations suggest that births will recover due to a catch-up after a birthing deficit during the pandemic. There were three years where fewer babies were born relative to the natural trend. We had the privilege meeting with a statistical demographer during our trip who expects 70% of the 3-year birth deficit to be caught up in 2024/25.

Source: Harbour based on meeting notes from demographer meeting.

If this prediction is correct, it presents a once in a multi-year period for infant formula companies to connect with consumers. Chinese mothers tend to feed formulated products to their children many years beyond the toddler stage and are often very loyal to the brands they select. Hence, a short-term increase in births could benefit an infant formula company for years to come as babies graduate to toddler formula and beyond. One of the mothers in a focus group we organised told us she intends to feed her child formula to adulthood – or for as long as the child accepted it.

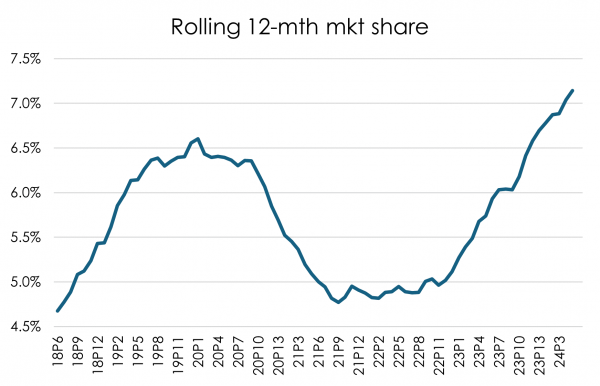

Having met the wider a2 Milk China management team, it is clear that there is depth in the team across critical functions, like distribution, sales, marketing, data and strategy. Execution also appears to be very strong currently, going from record to record in terms of market share. Whilst the overall infant formula market has declined (volumetrically) for a number of years, this decline is showing signs of slowing. This might be a sign that the demographer’s theory is correct and we’re seeing early signs of improved births.

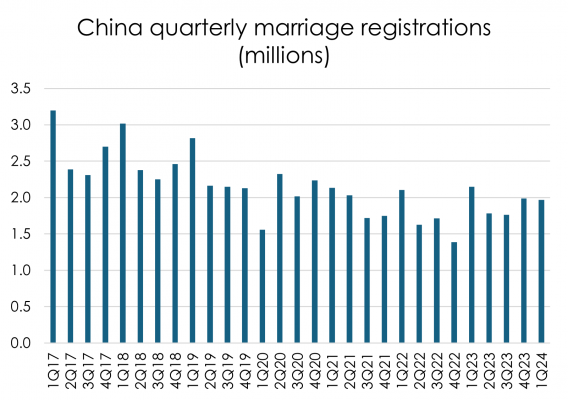

One strong predictor of births is the number of marriages. There are strong cultural and economic reasons for getting married in China before having a child, and the correlation is strong between marriages and new births (one year later). Hence, we were encouraged to see a strong growth in marriages in the December 2023 quarter. However, the drop in the marriage registration data in the March 2024 quarter came as a surprise as the feedback from being in China is that wedding venues are fully booked for months ahead.

The data can be volatile and smoothing over time might be more useful, which then points to a 12% increase in marriages over the last 6 months (December 23 + March 24 vs the same period a year earlier). However, most disappointing is that the March quarter is typically the best for marriage registrations with an approximately 30% share of annual marriages, which makes the annualised number of marriages using historical proportions look anaemic.

Source: Ministry of Civil Affairs China

When looking at how a2 Milk is navigating this fluid industry, it is fair to say they have done an exceptional job at rebuilding the franchise after having its biggest distribution channel (personal shoppers or daigou) disintegrate during the pandemic. It is back well and truly, printing a record market share and has reshaped the distribution to more sustainable channels like physical stores, cross-border e-commerce, and online to offline sales.

Source: Harbour, Kantar

This sets them up nicely to capitalise on a potential short-term increase in births, although risks remain whether this will transpire given the weak March-quarter marriage data. Similarly, we are coming towards the end of a consolidation period where brands like a2 Milk have benefited from smaller brands exiting the market as they had either failed to gain a licence to operate in China from the regulator, or their sub-scale business models forced them to exit. Hence, it is plausible that the recent strong market share gains will moderate going forward as competition between the remaining brands intensifies.

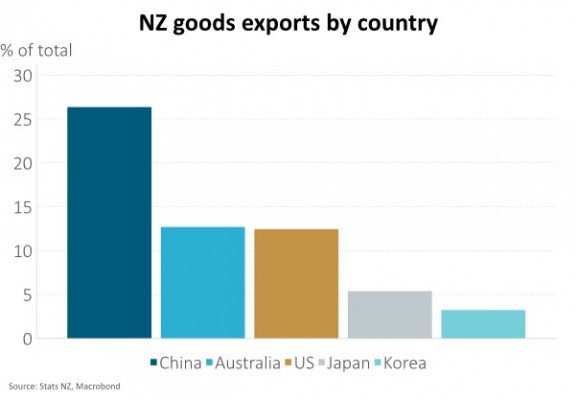

Of course, a2 Milk is only one company heavily influenced by how the winds are blowing in the Chinese economy and at the mercy of long-term demographics. But China is well and truly our largest goods trading partner – bigger than our second and third biggest combined – and if structural forces will offset some of the cyclical and potential upside from Chinese economic activity, we will feel it across the country. Australia, as our second largest trading partner also trades heavily with China and hence, we are exposed twice to the same risk.

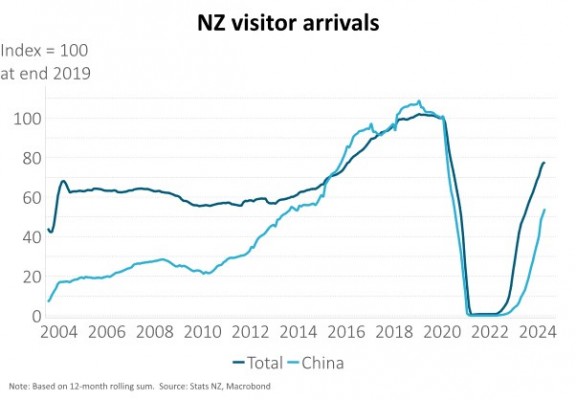

Dairy, meat and wood are New Zealand’s three largest exports to China, and these have all been weak in the last 12-18 months. On the services side of the economy, tourism is the biggest export to China with education a distant second. Neither have recovered to pre-pandemic levels and tourism has only regained half of its market share of visitors to New Zealand. This will hopefully change soon as more airline capacity comes online. It is clear to us that Chinese consumers hold New Zealand high on the list of desired holiday destinations, although worries about their own domestic economy could delay the recovery in tourism.

We are monitoring the risks and news flow closely. In the very near term, we are looking to China and the upcoming CPC Central Committee’s plenary session in July for policy initiatives to address some of the longer-term structural drivers of the economy, such as Hukou reform and perhaps family expansion incentives. Similarly, the all-important property market has been in a state of flux for years and any credible initiatives to stabilise property will be welcomed precursors to getting the consumer’s growth story and confidence back on track.

Harbour Asset Management Limited (Harbour) is the issuer of the Harbour Investment Funds. A copy of the Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://www.harbourasset.co.nz/our-funds/investor-documents/. Harbour is also the issuer of Hunter Investment Funds (Hunter). A copy of the relevant Product Disclosure Statement is available at https://hunterinvestments.co.nz/resources/. Please find our quarterly Fund updates, which contain returns and total fees during the previous year on those Harbour and Hunter websites. Harbour also manages wholesale unit trusts. To invest as a wholesale investor, investors must fit the criteria as set out in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.